THREAD #68

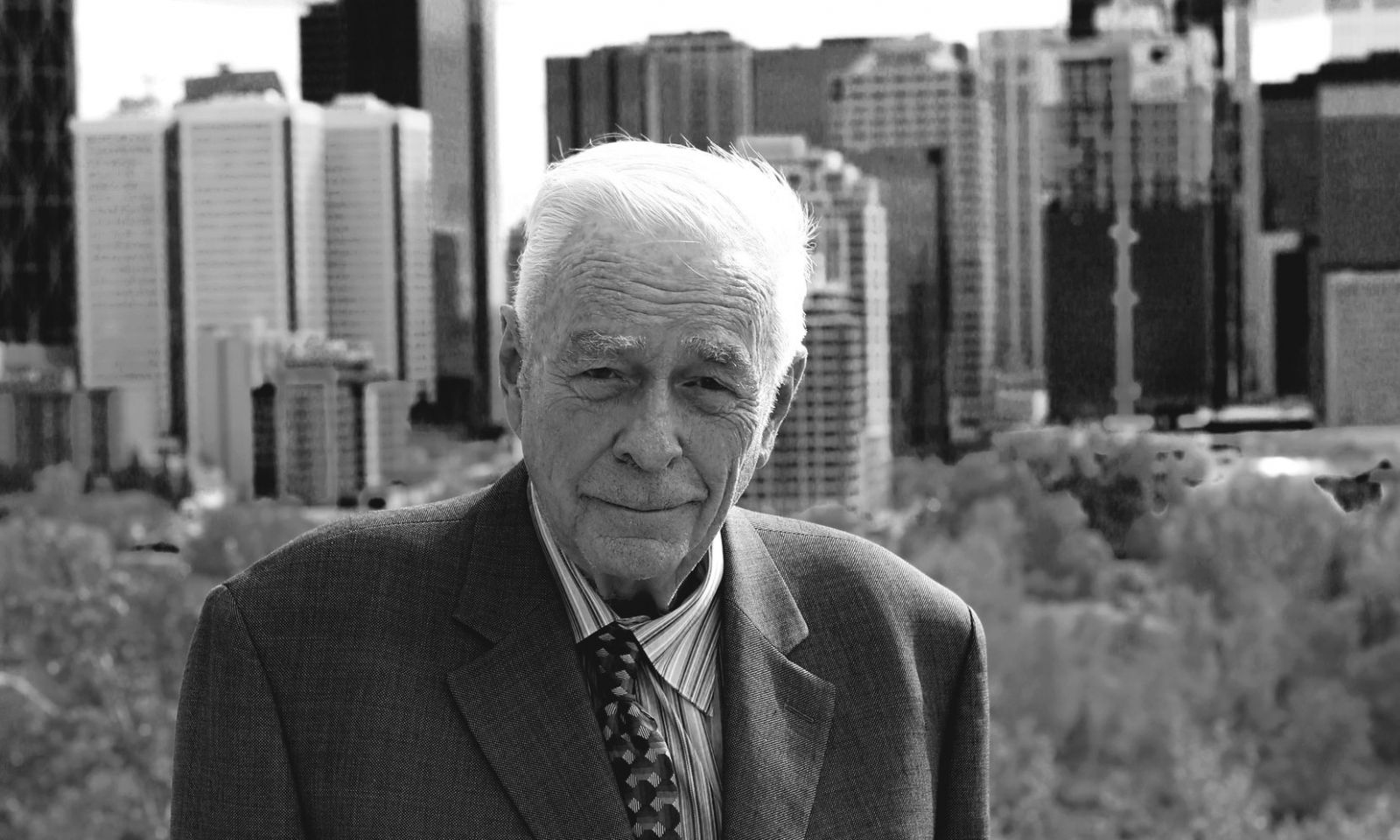

Edward Byfield

October 21st, 2016

Each week on the Thread, we feature a Canadian leader whose leadership position is inseparable from their faith. The profiles draw on the work done by our senior editorial advisor, Lloyd Mackey, in the Online Encyclopedia of Canadian Christian Leaders as well as presenting new stories from writers across Canada.

by Nigel Hannaford

Edward Bartlett ‘Ted’ Byfield (born 1928) is an Alberta newspaperman, educator, publisher of the influential Alberta Report Magazine, and of a 12-volume book series on the history of Christianity. Also widely acknowledged as a founding father of late twentieth century Canadian conservatism, Byfield’s sometimes unholier-than-thou leadership style was unique, effective and generally evokes pleasant recollections from those led.

Born and raised in Toronto, Ted Byfield had a nominally Anglican mother and an atheist father.

In 1946, the family moved to Washington D.C., where the seventeen-year old Byfield worked as a copy boy in the Washington Post. Returning to Canada two years later, he became a reporter at the now-defunct Ottawa Journal.

There he met summer intern Virginia Luella (Ginger) Nairn: When Byfield was appointed news editor at the Timmins Daily Press, in northern Ontario, she followed him. They were married in 1949.

As a rookie journalist, Byfield quickly showed the enterprise for which he was later famous. His first front-page story at the Washington Post reported on a Brooklyn bus driver who at the end of his shift, absconded to Florida in one of the company’s vehicles.

Asked why, he said, “Ask the guys at the depot. They’ll understand.”

Byfield checked at the Washington depot. He recounted later, “The drivers all said, it’s because of the [expletive] who ride buses.”

Later, in Winnipeg, he hid in an air-conditioning duct to overhear city council discuss a scam involving municipal funds.

He and Ginger became Christians in the early fifties, after reading the works of G.K. Chesterton and C.S. Lewis. They began attending Winnipeg’s St. John’s Anglican Cathedral and characteristically, launched themselves wholeheartedly into the life of the body. First they joined the choir. Soon, they were teaching Sunday school, and it was in this capacity that Byfield made a life-changing friendship with fellow chorister and teacher, Frank Wiens. Neither was pleased with the Sunday school: Irregular attendance, staff turnover and deficiencies in the physical facilities all contributed to what Wiens and the Byfields considered disappointing results.

However, Byfield and Wiens saw in the tepid participation of students and staff, evidence of a more serious problem. Their decision to do something about it was pivotal in both of their lives.

In their view the tenets of faith were poorly understood and weakly held, because students were simply unaware of their history. Worse, they were not taught to think: Few youngsters seemed able to follow a premise to its conclusion.

As for the inspiring idea that life was a pilgrimage with all the implied attendant joys, struggles and rewards, this was no longer commonly respected in an affluent, pleasure-seeking society.

They concluded that at a time when it was deeply needed, Christian leadership was atrophying.

Their solution was to be a full-time boarding school for boys. There, the necessary qualities to live a triumphant Christian life could be imbued at an early age. Robust training of the mind would be complemented by rigorous development of the body.

Accordingly, when not in class, students undertook lengthy expeditions on foot and by canoe through northern Canada’s wilderness. Many have commented since that their experiences on these journeys, and the values they instilled – teamwork, confidence and God-reliance – had informed their entire lives.

Above all students would be taught Christianity’s history and heritage, as a living guide to the future. Students would thus not merely be taught to graduate; they would be taught to live life.

Ted Byfield (right) with St. John School students at Norway House, celebrating the end of a 350 mile canoe traverse of Lake Winnipeg.

The interim step was a weekend school. The results won popular support in Winnipeg so that by 1962, the Byfields and Wiens were able to open the first St. John’s school, near Selkirk, Manitoba. For administrative purposes, it came under the umbrella of the Company of the Cross, an Anglican lay order responsible to the Bishop of Winnipeg. This too was established by Wiens and the Byfields, as a framework for communal Christian living that would support staff deeply committed to raising the next generation of Christian leadership. Initially, staff worked for a dollar a day, and all found. True to its mission, St. John’s advertised itself as ‘the toughest school in North America.’

At this point, Byfield gave up reporting for the Winnipeg Free Press to teach history full-time at Selkirk. The concept caught on: The St. John’s school in Manitoba would be followed by others like it in Alberta, and Ontario.

With the schools established, Byfield embarked upon his wider ambitions to influence society for God.

Returning to journalism in 1973, he began work on a news magazine in the format of Time and Newsweek, but with an open, unapologetic Christian viewpoint. The result was the St. John’s Edmonton Report. It opened in 1974, again under the aegis of the Company of the Cross, and with the same ethos of communal living and the same compensation formula that underpinned the schools.

Eventually the difficulties of attracting and retaining staff would oblige both schools and magazines to offer regular salaries. But in the words of Ted Byfield, whatever the compensation package, St. John’s Edmonton Report, St. John’s Calgary Report, Alberta Report, B.C. Report and finally Western Report, covered national events for thirty years “as if Christianity were true.”

Those who know the Byfields well, especially those who worked for them, assert that the enduring success of these publications owed a tremendous amount to ‘Ginger’ Byfield. Apart from raising six children and providing food and shelter to whatever waifs, stray and refugees Ted brought home, she was a key part of the Report operation.

In the first place, she was a fine writer. However, many ‘Report’ alumni also remember her as an exceptional editor, and a towering influence in the newsroom.

Indeed, she is credited with having a steadying effect on her sometimes impulsive husband. Their son, the late Link Byfield, recalled: “My dad, as most egocentric geniuses do, has the habit of going off course in new and dangerous directions, while my mom ends up doing most of the work… He was the wind in the sails and she was the rudder.”

Whatever their internal dynamics, the magazines carried enormous political clout from Manitoba west.

For many westerners during the late twentieth century, conservatism and Christianity were overlapping causes. The Report magazines were faithful to both.

Their meat was Canada’s increasing secularization: They deplored Supreme Court activism and the ‘gay agenda’ it endorsed. They supported the pro-life struggle, excoriated the injustice of human rights commissions and above all, the intentional rejection of all absolute truths and moral principles in public education.

This advocacy did not go unacknowledged. In September 2011, then-prime minister Stephen Harper sent a message to a Report reunion, praising Byfield for having done ‘so much to inspire, inform and lead the conservative movement in Canada.’

Not surprisingly, they became a political vehicle for the widely shared western view, that oppressed by federal Liberals and betrayed by the Mulroney-era Progressive Conservatives, westerners had no voice in Confederation.

When Preston Manning launched the Reform Party in 1987, he therefore did not have far to look for vocal support. Indeed, as keynote speaker at the Vancouver Western Assembly in 1987, Byfield made first public use of what would become the Reform Party’s battle cry, ‘The West wants in.’

This advocacy did not go unacknowledged. In September 2011, then-prime minister Stephen Harper sent a message to a Report reunion, praising Byfield for having done ‘so much to inspire, inform and lead the conservative movement in Canada.’

Despite the initial low labour costs and the enormous popularity of the magazines in conservative Alberta – in 1985 circulation peaked at 53,277 – the Reports were not consistent moneymakers. The last of them closed in 2004. That they lasted as long as they did was a tribute to Byfield’s legendary ability to persuade sympathisers who believed as he did, to fund the larger cause.

But by then 74, the indefatigable Byfield was already on to other things. He had already published the first of his two legacy histories – that of Alberta from the earliest times to the year 2000, in twelve volumes. His attention was now directed to an equally monumental tribute, the whole story of 2,000 years of Christianity. The set, part narrative, part polemic, was finally published in 2013, also in 12 volumes.

Worried by what they perceived as the spiritual drift of the Anglican Church, Ted and Virginia Byfield dropped their connection to it in 1996, adhering to the Orthodox Church in America.

Ted Byfield is predeceased by his wife Virginia, whom he praises as his ‘best friend, best editor and best drinking partner,’ and by two of their six children.

But what always set Byfield apart whether in a classroom or in the direction of his magazines and encyclopedic histories, was his ability to interpret the zeitgeist of his times from a Christian perspective.

It is not the least of Byfield’s accomplishments that the Canadian newspaper industry is well-seeded with former Report employees, some at very senior levels. (Report staffer Paul Bunner went on to manage Prime Minister Harper’s speechwriting department from 2006 to 2009.)

While their shared experience should not imply a common point of view, Byfield’s influence crossed the spectrum. Many have written of his famous ‘rants and rages’ as deadlines approached, the staggering workloads, the long hours and the sacrifices demanded to keep the magazines afloat in difficult circumstances.

But, they have also catalogued puzzling contradictions. A newsroom volcano perhaps, but generous to a fault… Fiercely opposed to the spiritual roots of gay activism, yet accepting of gays as friends and employees… driven, yet only by the passion to evangelize and defend the name of Jesus in a society he believed was walking away from Him. And always there was whisky when the job was done.

He mellowed in later life. But what always set Byfield apart whether in a classroom or in the direction of his magazines and encyclopedic histories, was his ability to interpret the zeitgeist of his times from a Christian perspective.

As he himself would later reflect, ‘We are swiftly abandoning many of the fundamental social and moral principles upon which our civilization is based. That is, we’re zealously cutting off the branch we’re sitting on…very few people, whether educated or uneducated, know where those principles came from, and how we came to embrace them. We are dangerously ignorant of our own heritage and history.’

Byfield’s work has been based on the premise that governments respond to the public will. He reasons – correctly – that if the secular tide is to be turned, it will be through educating Canadians about their Christian heritage and what they risk when they reject it. Only when Christians show that it matters to them, can they make it matter to politicians.

In his late eighties, the now-iconic Byfield remains active in this calling, developing writing skills for students affiliated with the Alberta Home Education Association.

The objective? A new generation of Christian writers, able to defend and proselytize for their faith in an increasingly hostile media climate.

-

Nigel Hannaford is a former newspaper executive and member of the Calgary Herald editorial board. From 2009 to 2015, he managed Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s speechwriting department. Hannaford earned a BSc in political and international studies from Southampton (England) University in 1969.

Help us spread the word