THREAD #119

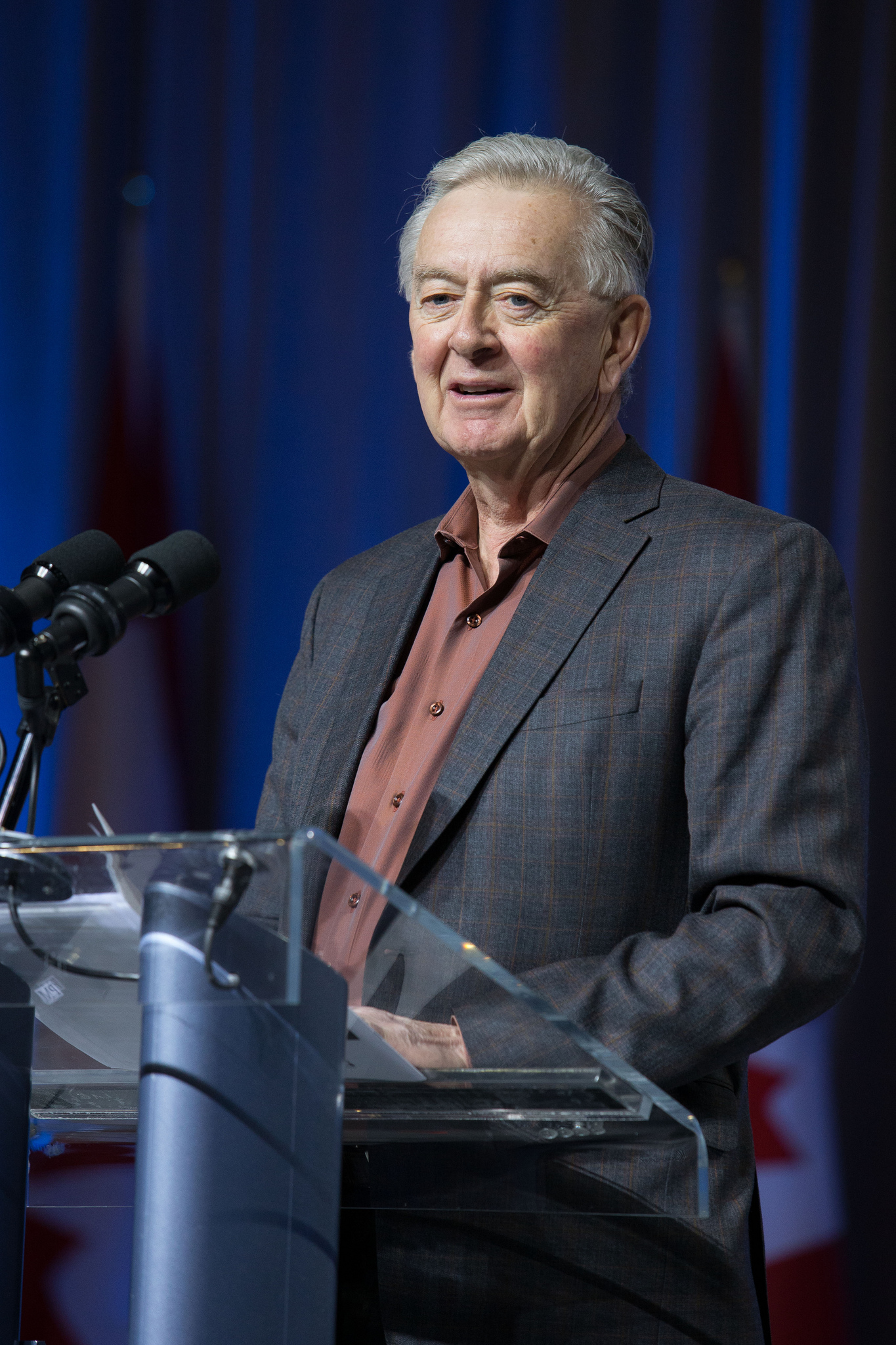

Preston Manning

April 28th, 2017

By Lloyd Mackey

Preston Manning came by his interest naturally, in what he calls “navigating the faith-political interface.” His father, Ernest C. Manning was premier of Alberta for over two decades in the mid-twentieth century. During that time, he was the voice of Canada’s National Bible Hour (CNBH) – which attracted 600,000 listeners weekly, nationwide.

During the 50s and 60s, when the younger Manning was in high school or studying physics at the University of Alberta, he would deliver short talks and, occasionally, the main message on CNBH. The objective was to draw the interest of possible younger listeners, focusing on the practical, ethical and evidence-based implications of the Christian gospel.

This writer can recall hearing some of those messages and being struck by the slightly different emphases of father and son. Ernest Manning would talk about theological matters, among them Bible prophecy and its relationship to national and international matters. His son would focus on the relationship of science and faith, or ways in which Christianity could help people as they lived in community. Both men held to the idea that God was interested enough in human beings that his son, Jesus, had entered into human history to bring meaning and purpose to life.

Ernest Manning began his own distinguished public service in the 1930s when, as a Saskatchewan farm boy, he heard William Aberhart of the Calgary Prophetic Bible Institute (CPBI) on a crystal radio set he had assembled. Aberhart’s presentation attracted him to the Christian faith and, not long after, Manning moved to Calgary to study at CPBI.

There, he met Muriel Preston, the pianist for the school and its radio program, whom he later married. Preston Manning was the younger of Ernest’s and Muriel’s two sons. Keith, the older, suffered from cerebral palsy, grew to adulthood, then passed away in 1986 at age 47. Meanwhile his life and struggles taught his younger brother much about sibling care and compassion.

But back to the story: Ernest Manning, in addition to learning about the Bible, became interested in an economic and political theory called Social Credit, being encouraged by Aberhart. The Socred concept spread like prairie fire in Alberta – a little ahead of the social gospel concept eventually advanced by Baptist pastor Tommy Douglas in the neighboring province of Saskatchewan. In 1935, Aberhart became the Socred premier of Alberta. He passed away in 1943 and Manning, by then Aberhart’s provincial secretary, advanced to the premiership – just months before Douglas achieved the same status in the province to the east.

The senior Manning held the Alberta premiership for the next quarter-century, then served in the Canadian Senate until he was age 75, in 1983. He died at 87 of congestive heart failure, in 1996, but not before watching his son, Preston, put the first pieces of a project into place that would reshape the whole centre-right part of the national political spectrum. Now, approaching his own 75th birthday, the younger Manning still leaves his imprint, through the Manning Centre for Building Democracy.

While the Manning and Douglas ideologies were, respectively, set in the right and left sides of the political spectrum, they were sometimes more similar than different. Manning would tend to emphasize, in political matters, that government was a “facilitator”; Douglas believed that the social gospel was meant to reshape society by direct state action. But they both saw the Christian gospel as potentially transformative, both on a personal and social level.

There was a gentleness to Douglas’ approach, however, that did not help the New Democratic Party when he became it founding leader in 1961. Veteran political journalist Allan Fotheringham, writing in Malice in Blunderland (1982) said that Douglas’ prairie populism lacked the “radical urban hatred” required to lead a federal social democratic party. “Baptists don’t hate,” he said. “But they don’t let down the barriers, either.”

Manning’s original objective, when he went to university, was to study physics. But, much as he loved science, he became intrigued with public life and switched his major to political economy. Along the way, he met a young nurse named Sandra Beavis. They married and eventually had five children.

When his father was still premier, Manning made a failed attempt to get elected as a Socred MP. Then, he settled in to working with his father shadowing in the background, in a management consultancy. One of his best experiences involved helping indigenous groups and oil companies to interface in the Slave Lake area. It became a part of his growing understanding of the subject of community development – and the respective roles played in such development by businesses, governing bodies, faith groups, and other such institutions. Although Cardus, the developer of Thread of 1000 Stories, was still years from formation, the work it would eventually do on social architecture’s role in the development of cities, had some similarities to Manning’s community development concepts.

In 1967, Canada’s centennial year, Ernest Manning penned a slim volume entitled Political Realignment: A Challenge to Thoughtful Canadians, in which he encouraged a moving together of the various strands of political conservatism. The younger Manning, although not named as a co-author, admits to having had substantive input to the book.

Over the years, there was an ebb and flow of interest in both the collaboration of various conservative streams and the Manning-inspired encouragement of evangelical Christians to get involved in the political process. Indeed, after PC prime minister Brian Mulroney came to power in 1983, he would sometimes give a nod to those 30 or so western MPs that identified as evangelicals – dubbing them affectionately as his “God Squad.” Chief among them was Jake Epp, a Manitoba Mennonite who became Mulroney’s health minister.

Managing a God squad was a bit like herding cats, however. One of the consequences of such was that when western interest began to coalesce around Manning’s interest in developing the Reform Party of Canada, in the late 80s, many of those Christian political aspirants liked what they saw in the new party.

So, in 1993, the Reformers elected 52 MPs, almost all from the west – many of whom would have been Conservatives, if they had been around earlier. And many, too, were these Manning-motivated evangelical Christians, who trusted this self-effacing but thoughtful son of the former Alberta premier.

There was a fair amount of friction between the PCs and Reformers, which, in effect, made the Liberal return to power, this time under Jean Chretien, much easier. (The emergence of the Bloc Quebecois, which competed with the Reformers for dominance on the opposition benches, was also a major factor in PC disenchantment.)

Manning led the Reformers from 1987 to 2002, entering the House of Commons himself in 1993. During that time, he also nudged his Reform “movement” toward a broader grouping called the Canadian Alliance. Much of his leadership in this process could be easily traced to the thinking he did years before when he helped his father write Political Realignment.

The re-emergence of a broadly-based Conservative party had some difficult moments. Manning ran for the leadership of Canadian Alliance but lost to Stockwell Day, another evangelical but one who had been finance minister in the Alberta PC government. As such, Day tended to attract support from Conservatives who might have been disillusioned by the sense that Manning was too strong an adversary to bring about a united conservatism, despite his political realignment bent.

That said, it should be noted that Manning had quietly encouraged Day to consider federal politics and had, reflecting Jesus’ teaching and example, prepared for the possibility that he would need to “sacrifice” his own longer term leadership ambitions. Simply put, he would suggest that when the intended reconciler finds that he or she is an obstacle, it is time to step aside.

Day himself ran into difficulties after he became CA leader. The Conservative caucus had begun to grow again, moving from a membership of two to the mid-teens. CA MPs Chuck Strahl and Deb Grey, both encouraged in the faith-based conciliation approach, began a rapport with the PCs, with Strahl, particularly, forming a friendship with Peter MacKay, who was emerging into the leadership role of the Conservatives. (MacKay, it should be noted for the record, was also shaped by significant Christian pastoral care, albeit of an east-coast Presbyterian variety. It was strengthened later, when he married Nazanin Afshin-Jan, a deeply committed Christian activist.)

The temporary coalition which emerged from Strahl’s and Grey’s efforts emerged in 2001-2002 and was known as the PC-DR parliamentary group. (DR stood for Democratic Representative.) It was after MacKay became PC leader in 2003 and Stephen Harper succeeded Day as CA leader, that the coming together occurred, forming the Conservative Party of Canada.

Once Manning retired from the House of Commons in 2002, he worked behind the scenes to encourage the 2000s version of political realignment, then set up the Manning Centre for Building Democracy. MCBD has become well known for its late winter Ottawa gathering known as the “Manning Conference” in which “movement conservatives” are encouraged talk and act in ways that will enhance their objectives. And he has had a hand in developing the Clayton H. Riddell Graduate Program in Political Management at Carleton University. One of the people who led in the development of and teaches in that program is Paul Wilson, a Queen’s history PhD who worked in the public policy area for both Manning and Harper. Wilson also was founding director of faith-based Trinity Western University’s Laurentian Leadership Centre, housed in a former lumber baron’s stately mansion a short walk from Parliament Hill.

For Manning, think-tanking is an important activity for people who want to help shape public policy and political development. He likes to point out that the Broadbent Institute, developed by former and respected New Democratic leader Ed Broadbent, was based on concepts also shaped by MCBD. The faith-component of BI draws some influence from Bill Blaikie, a United Church minister from Manitoba who served as deputy NDP leader under Jack Layton and actually co-wrote some of Layton’s statements on faith and social values. So, while they frequently head off in different directions ideologically, the two “tanks” major in thoughtful approaches to public policy, at times rooted in faith-shaped values.

In many ways, MCBD and other post-parliamentary activity has enabled Manning, in effect, to do some of the same kinds of things that American president Jimmy Carter did, after he left office. Baptist Carter, now in his 90s, regularly teaches a Bible class in his home church in Georgia. And, for years, he led “builds” around the world for faith-based Habitat for Humanity. HfH, briefly, helps people who could not otherwise afford a house, to join a community in “sweat equity” to provide a quality home for their families. And it does so using the “theology of the hammer” enunciated by Habitat founder Millard Fuller

Manning and Sandra practiced this kind of thing with their own children, as they grew to adulthood. They would provide them with opportunities to serve with an overseas non-government organization – often faith-based. Thus, those young adults could learn what links nations together in the spheres of faith, the economy and community leadership.

Manning has continued to write about “navigating” the faith-political interface. His subjects were rooted in the biblical stories of Jesus, Moses and the Hebrew leaders during times of exile. The leadership lessons from those figures have played effectively at various times, not only in the political sphere but in such educational institutions as Regent College in Vancouver and Tyndale University College and Seminary in Toronto.

And, in appropriate settings he has provided resources which could enable Muslim political aspirants to understand the faith-political interface in Canada, as well as in other countries where Muslim people interact increasingly with people of other faiths – or no faith.

Sandra Manning, too, has helped shape some of Preston’s post-parliamentary thinking. She has aligned herself with A Rocha, a Christian environmental organization which attempts to bring a faith interface to such issues as climate change. The Manning approach has brought respect for an environmental conservation/conservative approach from such as Katharine Hayhoe, the Toronto-reared, highly influential co-author (with her pastor husband Andrew Farley) of A Climate for Change: Global Warming Facts for Faith-Based Decisions (FaithWords, 2009)

Castle Quay Books, a Canadian faith-based publisher is presently putting together a comprehensive volume of Manning’s writings in the areas of “leadership lessons” which have come out of his own political, community development and faith journeys.

He confesses to emphasizing repetitively, the biblical idea that Christians in public life need to be “as wise as serpents and as gracious as doves” – rather than the other way around. The devil, as represented by the serpent, is very sharp, wise and or clever. There is no reason for the believer to be any less so – but to do so graciously.

And he speaks, in his study of Jesus’ leadership concepts, of being both reconciling and incarnational. By the latter, he means that, just as Jesus came to live among us, so we should be comfortable with living among and interacting with people and groups who are different from us.

At times, Manning’s critics have, in my modest view, been unfairly critical of his “sacrificial” and “incarnational” concepts. It is his self-effacing and modest nature that tends to disarm the idea that he might have a slightly messianic outlook. For what it is worth, it is that rather deep modesty, shaped by a keen sense of disarming humor that helps people to listen, when otherwise they might walk away.

One example: When asked about his spiritual influence on Stephen Harper, Manning said he could not remember ever talking to him about his faith. But Harper biographer John Ibbitson quotes Tom Flanagan, sometime advisor to the former prime minister. Flanagan “recalls Harper telling him that Manning’s example of living a Christian life without trying to impose that life on others deeply affected him.”

Further reading

Ibbitson, John. Stephen Harper,Signal, McMillan & Stewart, Toronto, 2015. Chapter 8, “Faith”.

Mackey, Lloyd. Like Father, Like Son: Ernest Manning and Preston Manning, ECW Press, Toronto, 1997.

Manning, Ernest. Political Realignment: A Challenge to Thoughtful Canadians. McClelland & Stewart, Toronto, 1967.

Manning, Preston. The New Canada, Macmillan of Canada, Toronto, 1992

Manning, Preston. Faith and Politics Leadership Lessons from the Public Life of Jesus, Regent College Publishing, Vancouver, 2016

|

- Lloyd Mackey has close to half a century of experience in community, faith-based and leadership journalism, including 15 years working out of the Canadian Parliamentary Press Gallery in Ottawa. Books he has authored include These Evangelical Churches of Ours (Wood Lake Books, 1994), Like Father, Like Son: Ernest Manning and Preston Manning (ECW, 1997) More Faithful than We Think: Stories and Insights on Canadian Leaders Doing Politics Christianly (BayRidge Books, 2005) and The Pilgrimage of Stephen Harper/Stephen Harper: The Case for Collaborative Governance (ECW, 2005/2006). He is founding editor/director of the Online Encyclopedia of Canadian Christian Leaders, an outgrowth of his Doctor of Ministry (DMin) studies, completed in 2015 through Tyndale University College and Seminary. In 1984, he earned a Master’s in Business Administration (MBA) at Simon Fraser University. He and his wife, Edna, are trying to practice “active retirement” and an examination of “social architecture” in the emerging Central City urban core in Surrey, BC. |

Help us spread the word